Written by Dr. Patrick Gill, Rambus Principal Research Scientist

From its inception, the Internet has been revolutionary in the way it moves data. Let’s explore what makes the Internet so effective, and determine if we can implement a similar revolution for physical goods manufacturing.

Data Transport

Firstly, the Internet abstracts away the entire physical layer of how data is actually transported. Currently, anybody can come up with a new method of transmitting data. People would start using it tomorrow – without necessarily being aware that a new technology had been deployed.

Secondly, procurement is automatic and universal on the Internet, as one does not need to make arrangements with any physical individual to use transmission lines. Thirdly, Internet Protocol is completely indifferent to the packet contents. The same protocol can be used to transmit video, text messages, bank details, inventory levels, code; you name it.

A brave new hardware world

So, what does this have to do with hardware? Well, let us imagine a world where we manage to recreate the above three revolutions for physical items. First, visualize a manufacturing flow where people (or their software agents) could specify end-goal design requirements for a product, with the physical instantiation of the tooling needed to make it happen becoming as irrelevant to humans as the copper, radio or optical fiber used to transmit this article.

Second, think about a system where bidding for the production of the tooling to make a product is as automated as the router systems used to shunt data over the Internet. Prices would fall towards costs pretty quickly, and the most useful manufacturing technologies would scale, driving costs down further in a spiral of goodness. Third, imagine if the language used to specify the creation of things were universal; either based on an ISO standard or (more likely) a living reputation-based, crowd-sourced standard à la Wikipedia. Your software agents could then specify what the product has to do and how it’s made; any manufacturer’s software agent could automatically generate a quote.

Reimagining physical object design tools

Today’s physical object design tools are relatively cumbersome compared to what they could potentially be. Typically, you need to design each physical part with a visualization tool. The analogous process with Internet-based data transmission would be writing every email as a binary string, including MIME headers, which would be quite cumbersome. Nobody does that for data and the industry shouldn’t accept a similar level of tedium when specifying objects. Good AI-assisted physical CAD tools – or perhaps even an open ecosystem of them, could take places analogous to email clients and web browsers.

Indeed, imagine a world where advances in manufacturing technology (such as 3D printing), robotics, materials science, metallurgy, sensors, fabrics and microprocessors could be adopted immediately, with minimal human intervention. Similarly, envision a world where software agents compete to abstract away logistics problems of how to design, make and deliver finished goods at an appropriate scale. This would be a world where projects like the Raspberry Pi-based landmine detection hardware DOLPi could be envisioned simply by specifying their high-level objectives, with procurement and engineering handled by awesome next-gen CAD tools.

The Von Neumann-manufacturing link

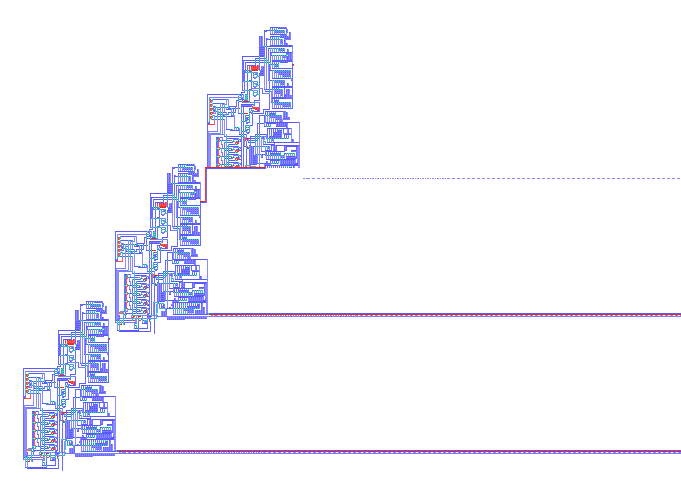

Can we realize this level of abstraction in manufacturing? We did it with computer programs; the Von Neumann architecture stores code as data, replacing the human-operated switchboards that prior computers required; advances in software compilers and frameworks continue to reduce the amount of a human’s time we need to build code that runs at near-optimal speeds for any piece of hardware.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

We did it with the Internet, as mentioned above; it’s highly eccentric to propose building any new model for shipping data of any type from place to place on Earth. We did it with computer services: gone are the days of startups demanding their own Sun servers in their own garages; now it’s so much easier to let cloud services procure your heavy computing needs automatically. We’re doing it with abstracting physical service procurement in the form of Uber and Airbnb. What will it take for atoms to be the next realm to adopt to widespread, universal automation?

AI & reputation management

We have a lot of work to get there, primarily in two disciplines: AI and reputation management. We need the AI agents to be capable of understanding real-world intentions as specified by a fallible (and non-technical) human being. We’ll require an extensive and open system of crosschecks and quality assurance; a robust reputation model (perhaps based on an irrevocable common blockchain, like Bitcoin) is key to being able to trust the components without many humans in the mix. In addition to these “hard” problems, we need a way to publicize and sell design services, quality control, new ideas and outwardly exposed AI smarts that can act as invention, procurement or design agents.

This transition would likely be slightly more difficult than initial industry adoption of the Internet. It’s much simpler to agree on whether data has been accurately transmitted over IP than it is to tell whether the physical goods you envisioned came out “right.” So let’s think about this in terms of a sliding scale. Are the AI agents are up to the task of providing enough intelligence and user-friendliness to meet the needs of “manufacturing?” Indeed, there are so many possible functional things to make, from bottle-openers to spaceships, with a huge range of complexity and risk to them – that there won’t be any kind of sharp boundary between a worthless AI and one that’s universally competent.

Automating CAD

A likely intermediate step would see expert human operators of CAD tools at the ready and producing bids on an open marketplace. As they refine their CAD tools to work more efficiently, there could be a gradual trend towards progressively less live human attention going into any given design. This could be achieved via the incremental adoption of machine-readable specifications describing materials and services, coupled with increasingly sophisticated design tools and components that are economically aware enough to make reasonable business decisions automatically.

In a competitive world, the mix of money, automation and an abstraction that removes the limits to scale could be the catalyst for a powerful transformation force. In the next decade, I believe we’ll see a rise in automated negotiations for goods and manufacturing services; more products designed and made with less than 40 hours of human labor; a greater degree of product customization; and services based around (although perhaps not directly created by) computer-controlled universal manufacturing techniques such as CNC machining. Sometime in the next 20 years, a wildly successful product company will be launched without the direct knowledge of its owner, who might be an AI specialist with little knowledge in the field of the product “she” is selling.

Transitioning to material procurement automation

The world on the other side of the transition to material procurement automation is one of leisure and empowerment: anyone can command the production of any useful good they can imagine at close to the cost of production. Automation – and the hardware needed to support it – will allow widespread, exponentially increasing use of green and human-friendly technologies that are currently labor-intensive.

In the long run, it’s probably best for the industry to keep the systems open and competitive. To be sure, low costs and rapid sharing of better ideas should facilitate the design of agile, versatile products that are fun to develop. It’s an idealistic vision to be sure, but one we’re moving towards gradually. Those who have worked with me personally know I am a nut for automation – my job isn’t done until my .gds files nearly create themselves. It is this vision of widespread automation I’m working to enable – via the innovations and the computer-aided design software we’re engineering at Rambus Labs – to make today’s and tomorrow’s new innovations require that much less human toil, and let our reality catch up to the scale of our creativity and imagination.

Leave a Reply